Accessibility for Neurodivergent Learners

By: Natalie Taylor Hart

Accessibility is a critical component of ensuring that all target learners for a course, regardless of ability, can use and learn from our instructional materials. Implementing accessibility practices enhances the effectiveness and inclusivity of instruction. Many apps have helpful built-in tools to check technical components in documents. These often focus on color contrast, screen reader accessibility, appropriate labeling, and audio features. These are vital functions for creating an inclusive work environment, but accessibility is more of a framework than a checklist. To create accessible instruction, designers must consider the diverse needs of learners and the various ways they engage with learning.

Any group of target learners may include individuals who are neurodivergent. Neurodivergence refers to a variety of conditions that affect how people’s brains function, their perception, and their relationships with others. Neurodivergent conditions include autism, ADHD, dyslexia, social anxiety, learning disabilities, and many other conditions (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). Some aspects of neurodivergence present challenges, while others impart particular strengths. Many traits are simply different from those of neurotypical people. Neurodivergence exists on a broad spectrum of support needs and strengths that vary from person to person; however, there are commonalities that we can utilize in our learner analyses.

Let’s explore how three different learning theories intersect to help us include neurodivergent learners in course designs.

Universal Design for Learning® (UDL)

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that guides the design of learning environments to be accessible, inclusive, equitable, and appropriately challenging for every learner. Its ultimate goal is to support learner agency—the capacity to actively make choices that align with one’s learning goals. UDL revolves around three core principles that promote accessibility and success for all students (Universal Design for Learning | CAST, n.d.).

Multiple Means of Representation

Instructors present information in multiple ways to address the diverse learning needs of their students. This includes both the mode of delivery (e.g., books, online documents, videos) to enhance accessibility and the conceptual representation of content to engage learners and build shared understanding. This principle focuses on how learners access and comprehend information.

Multiple Means of Engagement

Fostering accessibility through engagement means considering both the physical, emotional, and social dimensions of learning. This includes how learners are motivated, how they participate, and how they interact with content and peers. Consider your views on participation, guidance, and learner autonomy: How are they encouraged to take initiative and remain invested in their learning?”

Multiple Means of Action and Expression (or Showing Proficiency)

How do learners demonstrate what they’ve learned or the skills they’ve developed? Are these demonstrations aligned with the context in which they would use the skill or knowledge? This principle describes how to assess learners fairly and set them up to do their best work in ways that are authentic to their needs and abilities.

UDL is not merely a checklist, but a comprehensive framework of considerations to help instructors and instructional designers create learning experiences that truly serve the learners. One tenet of UDL is that accommodations for specific individuals often benefit others as well. Visit CAST for a more in-depth look at UDL.

ARCS Theory of Motivation

While UDL describes access, participation, and performance in learning, another theory considers motivation—the elements that draw learners in to engage with the content. Keller’s ARCS Theory of Motivation (Keller, 2009) breaks down motivation into four actionable components:

- Attention- Instructors can promote motivation by capturing learners’ attention. They can offer surprise or humor, ask questions that tap into curiosity, and vary the instructional strategies to accommodate student interests and preferences.

- Relevance- Learners are more motivated when they understand the purpose of the learning goals and see how those goals align with their personal interests, experiences, and future aspirations.

- Confidence- Learners who are confident in their potential to succeed display higher levels of motivation. Instructors can build confidence by clearly defining what success looks like, providing structured support, and offering tasks that are appropriately challenging. Helping learners see the connection between effort and achievement is also key.

- Satisfaction- Participants who enjoy the learning activities tend to exhibit higher motivation. Constructive feedback and positive comments provide extrinsic rewards. Consistent enforcement of standards helps learners feel that they are evaluated fairly in comparison to their peers.Motivation, by itself, can be an abstract concept; however, breaking it down into these components makes it more actionable.

Intersecting UDL and ARCS

Consider the areas of overlap between UDL and ARCs. The relevance domain of motivation, in particular, overlaps with UDL. In fact, when motivation is lacking, that can be a learning barrier. If learners feel that the content is presented in a way that aligns with their interests and experiences, they are more likely to perceive it as relevant. Relevance can be created when learning goals (such as demonstrating proficiency) are clear and aligned with skills in which learners have confidence and interest.

The satisfaction and confidence domains are connected through the demonstration of proficiency, making assessments fair, challenging, yet achievable. Attention relates to the engagement principle by providing opportunities for inquiry and curiosity.

By integrating motivational factors from the ARCS model into the broader UDL framework, instructional designers can enhance both the accessibility and the appeal of learning experiences. Let’s examine one more theory that specifically relates to the motivation of neurodivergent individuals.

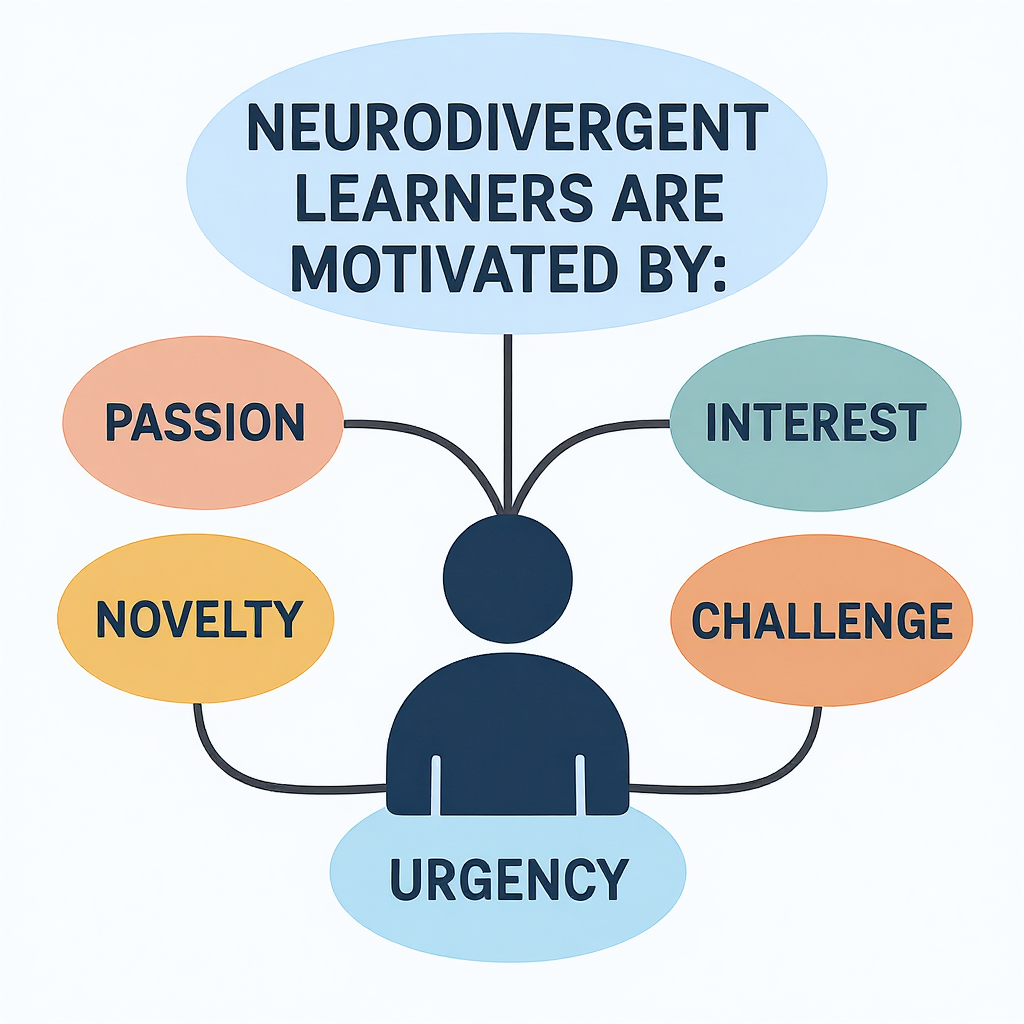

Interest-Based Nervous Systems

Neurotypical individuals are often motivated by a task’s perceived importance to themselves or others, or by the expected rewards or consequences associated with it. This can be called an importance-based nervous system. Many neurodivergent people are not motivated by importance. Dr. William Dodson described an interest-based nervous system that explains motivators for neurodivergent people, especially those with ADHD (How The Interest-Based Nervous System Drives ADHD Motivation – Neurodivergent Insights, n.d.). Instructional designers can utilize this theory to strategize effective instructional activities that cater to a diverse range of learners.

Some neurodivergent learners tend to be strongly motivated by passion, interest, novelty, challenge, and a sense of urgency (or a feeling of hurry), which can be represented by the acronym PINCH.

- Passion- Tapping into a learner’s passion is a powerful motivational tool. Passion can add meaning and purpose to a task or connect individuals with learning communities. It can provide opportunities for pride in accomplishment, underpinning Keller’s domain of confidence.

- Interest- If the content is inherently captivating to the learner, the instruction provides stimulation and immediate rewards.

- Novelty- New, unique, exciting, or provoking activities arouse curiosity and attention. Novelty can prevent monotony and reinvigorate engagement with familiar topics.

- Challenge- Some learners may be excited by challenging or competitive tasks where success is clearly defined for a problem or task that can be conquered. Note that if the challenge is too difficult, it will undercut confidence.

- Urgency- Time pressure can motivate some neurodivergent learners with feelings of excitement and adrenaline. They may bring this on themselves by doing work at the last minute. Use this motivator by breaking large tasks into smaller components with a series of smaller deadlines. They will experience urgency without the potential for overwhelm, and still have time to revise or build upon their work.

Not every neurodivergent learner will match this theory exactly. This theory describes traits found to different degrees in a broad group of people, rather than criteria for assessing neurodivergence in individuals.

Putting These Theories Together

When evaluating instruction, start by looking for unresolved barriers through the UDL lens. Then consider how the ARCS and PINCH motivational theories can drive participation, engagement, and commitment.

Let’s consider some examples.

- To support visually impaired learners, ensure that course materials are available in audio formats (UDL: representation). Neurodivergent learners find that listening to the audio version while following along in the written text helps them pace and maintain their attention, accommodating their difficulty with reading long texts.

- The course assessment (UDL: demonstrating proficiency) is designed as a simulation to mirror real workplace conditions. Some learners find this format more satisfying and relevant, enjoying the challenge and urgency of a realistic task. They prefer demonstrating their skills through action rather than answering abstract questions.

- A course uses polls and whiteboards for students to engage with peers and to measure their success against a larger cohort (ARCS: satisfaction). While some neurodivergent students in the group tend to show less participation in synchronous video calls, they have responded well to this asynchronous social engagement. In these settings, they exhibit higher levels of confidence because the rules for interaction are clear, and collaborative learning bolsters their ownership and passion for their debate positions and shared ideas.

The specific frameworks of these three theories, along with their intersections, help us tailor instruction so that all learners have meaningful access to learn and demonstrate skills.

References

Cleveland Clinic. (2022, June 2). Neurodivergent. Cleveland Clinic Health Library. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23154-neurodivergent

How the Interest-Based Nervous System Drives ADHD Motivation – Neurodivergent Insights. (n.d.). Neurodivergent Insights. https://neurodivergentinsights.com/adhd-motivation/

Keller, J. M. (2009). Motivational Design for Learning and Performance: The ARCS Model Approach. Germany: Springer US.

Universal Design for Learning|CAST. (n.d.). CAST. https://www.cast.org/what-we-do/universal-design-for-learning/