Aligning Design with Recognized Standards: Turning Three Shots into Two

Written by Steven Bradley and Dr. Angela Robbins

In instructional design, especially in client-driven environments, it’s easy to feel the pull toward output over outcome. Yet if our goal is genuine learner growth, the principle remains the same as in elite sports: quality beats quantity. Legendary golfer Bobby Jones said, “The secret of golf is to turn three shots into two.” In learning, just as in golf, focused, well-structured design can reduce friction and deliver better results. The key is aligning training with recognized quality standards so we move from churning out content to crafting purposeful learning experiences.

Designing for How the Brain Learns

Instructional design is based on how the brain naturally works. Our brains love patterns and often take mental shortcuts, like availability, anchoring, and representativeness. These aren’t mistakes; they’re ways the brain saves time and energy. Designers can create learning experiences that truly stick when they understand these shortcuts.

Instructional designers do more than create content; they design learning experiences. They take complex ideas and clarify them, helping learners reach understanding without feeling weighed down. In this sense, standards aren’t just red tape; they’re the trail maps that keep everyone on the right path.

Training Design Quality

When deadlines are tight and demand is high, it’s tempting to prioritize speed over substance. Still, in instructional design, especially in skill-intensive fields like healthcare, technology, sales, or sports, true effectiveness comes from building training that meets recognized quality standards.

As instructional designers, curriculum developers, and learning professionals, we’re more than content creators; we’re architects of learning environments. Our role isn’t just to share information; it’s to create the right conditions for real growth. And real growth only happens when it’s built on strong standards.

Why Standards Matter

In golf, and many other fields, it’s easy to think you know exactly how you’re doing, until the numbers tell a different story. When you track specific details like fairways hit, greens in regulation, putts, recovery shots, and penalties, you might discover that your real strengths and weaknesses aren’t what you thought. Sometimes, the skills we believe are our strongest are holding us back.

The bigger lesson? Even experienced professionals can fall into the trap of cognitive bias. The best way to avoid it is to measure progress against clear, proven benchmarks. In training design, those benchmarks include standards like Bloom’s Taxonomy, Merrill’s First Principles, Kirkpatrick’s Evaluation Model, and the Association for Talent Development (ATD) standards. Without them, we risk designing based on assumptions instead of focusing on what learners need.

From Content Delivery to Measurable Impact

High-quality training starts with a clear framework. That’s why it’s so important for instructional designers to anchor their work in proven standards. We’re not just delivering content—we’re turning goals into real growth. Whether it’s onboarding, compliance, leadership development, or technical skills, our role is to close the gap between what people know now and what they need to know next.

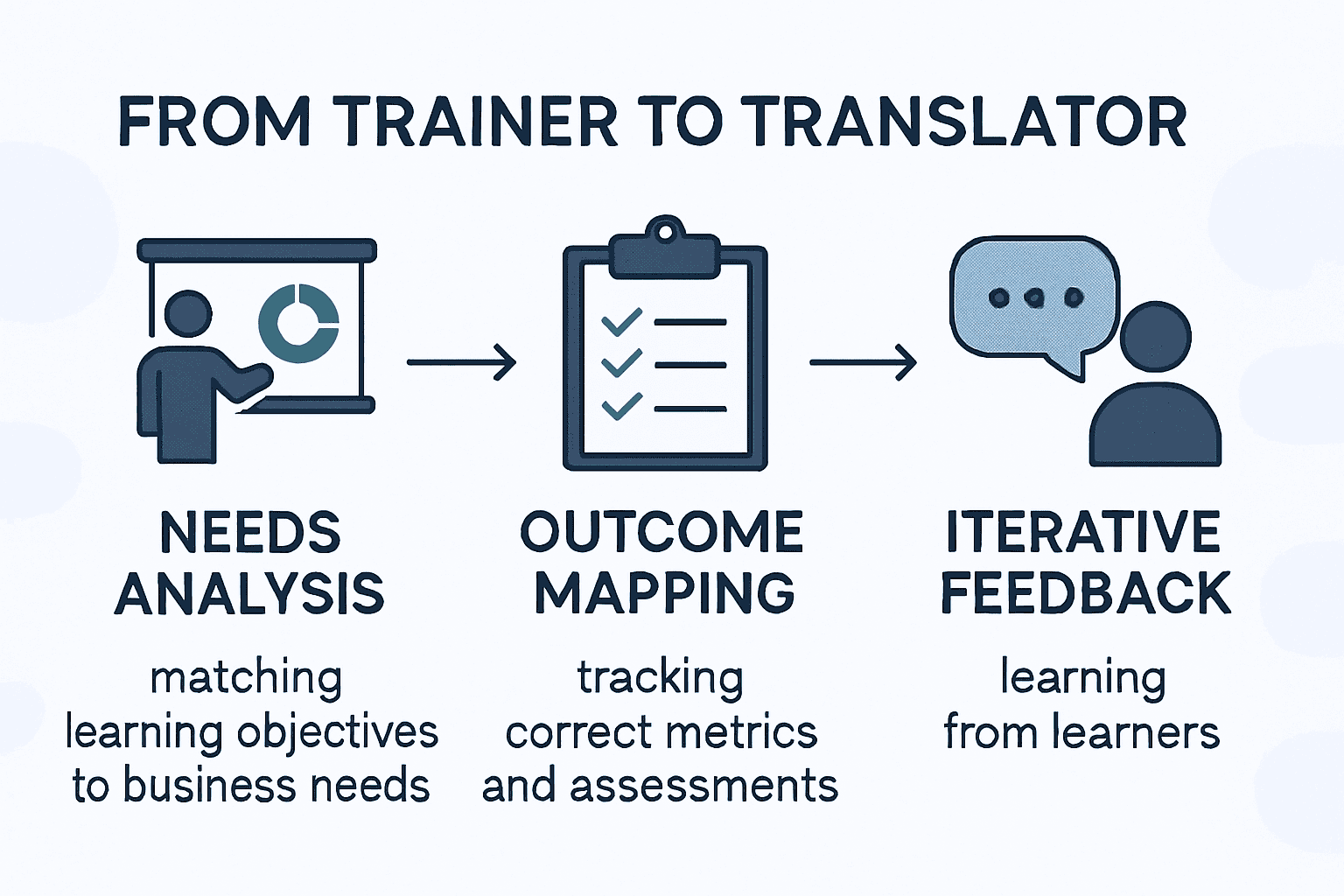

Making the shift from simply “training” to truly “translating” starts with alignment:

- Needs Analysis: Do our learning objectives directly support the business goals?

- Outcome Mapping: Are we tracking the right metrics and using the right level of assessment?

- Iterative Feedback: Are we listening to learners and making improvements along the way?

A course can look great and pass every visual design test, but if the outcomes aren’t clear, the results aren’t measurable, and learners aren’t challenged, it’s not quality training; it’s just a narrated PowerPoint.

Collaborative Learning and the Necessity of Struggle

The Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire argued that “the teacher and the taught together create the teaching” (Freire, 1968). This idea has never been more relevant than now, in an educational climate defined by rapid technological evolution, diverse learner profiles, and a growing awareness of how humans learn.

The future of learning is collaborative, dynamic, and rooted in personalization and resilience. As AI tools, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and culturally responsive pedagogies reshape modern education, it becomes even more critical to remember this: the foundation of effective instruction is built on meaningful struggle.

Learning doesn’t happen without challenge, whether in a classroom or on the golf course. This isn’t just about grit or perseverance; it’s a principle backed by research on how our brains develop. Freire’s vision of participatory education is especially relevant in skill-based learning, where instructors move from simply telling to guiding, helping learners discover, practice, and own their growth.

As educators use more inclusive strategies like UDL and AI-powered tools to meet different learning styles (Honey & Mumford, 1992; Fleming, 2006), the aim shouldn’t be to remove difficulty. Instead, it’s to help learners navigate it. Challenge isn’t the opposite of engagement; it’s what fuels it.

The Neuroscience of Difficulty and Learning

Modern cognitive science makes one thing clear: learning happens when the brain is challenged (Brown et al., 2014). Practices like retrieving information, applying it under pressure, and receiving feedback help build lasting skills. When difficulty is scaffolded effectively, it strengthens neural pathways and supports long-term retention (Bjork & Bjork, 2011).

In short, “desirable difficulties” create stronger, more adaptable learners. In sports instruction, for example, this might mean resisting the urge to immediately correct a player after one mistake and instead allowing time for trial, error, and self-adjustment before offering guidance.

This approach shifts the instructor’s role from director to facilitator. Effective coaches and educators recognize that overcorrection or constant intervention can undermine the learner’s ability to self-assess and adapt, key components of developing independent, resilient skills. Those who rely on quick fixes risk short-term gains at the expense of long-term growth.

The Real Standard is Growth

Whether it’s on the course or in the classroom, aligning training design with quality standards isn’t just about checking boxes, it’s about owning the responsibility to help learners truly on the course or in the classroom, aligning training design with quality standards isn’t just about checking boxes; it’s about owning the responsibility to help learners grow. The best instructional designers don’t shy away from challenge; they design for it.

Because real learning doesn’t come from making things easy, it comes from making them meaningful. And that’s when it sticks.

Author Bio

Steven Bradley is a contract copyeditor with eLearningDOC and a master’s candidate in Golf Teaching & Learning at Keiser University. A former journalist, he now focuses on building educational tools and content systems that support long-term skill development. He also teaches golf and believes learning is more about guidance than control.

References

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society, 56–64.

Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press.

Fleming, N. D. (2006). VARK: A guide to learning styles. Retrieved from http://vark-learn.com

Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Honey, P., & Mumford, A. (1992). The manual of learning styles. Peter Honey Publications.